Review (Theatrical): DJANGO UNCHAINED

DJANGO UNCHAINED (2012)

Dir-Scr: Quentin Tarantino

A Weinstein Company Release

A malformed pastiche comprised of equal parts loving movie homage and barbarous, bloody commentary on the dark violence in the American past and sometimes present, movie geek hero Quentin Tarantino’s latest work is a piece of flawed cinematic art that nonetheless demands attention and critical scrutiny.

Here, Tarantino concocts another in his series of ‘vengeance’ pieces that began with Kill Bill and continued now through both Death Proof, his half of the 2007 Grindhouse homage and box office flop, and his prior success, the Best Picture-nominated Inglourious Basterds. Made by and for fans of the so-called spaghetti western, a mostly-Italian subgenre of the American western that offers artistic peaks in the form of the grand Sergio Leone masterpieces and nadirs in the numerous knockoffs and B-movies that trafficked more in exploitation and low comedy, Django Unchained’s plot is classic and simple: An erudite and exceedingly cultured German bounty hunter and classic mentor character, Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) frees a cowed and broken slave named Django (Jamie Foxx) who can help him identify and bag the Brittle Brothers, and along with them a fat bounty.

Once this initial mission is satisfied, at the end of act one Django reveals that rather than enjoy his newfound freedom he must go on his own quest to find and rescue his wife Broomhilda (Kerry Washington) from whom he’d been cruelly and brutally separated by their former master (Bruce Dern, in a tiny but creepy cameo). Schultz says that because he owes Django one, he suggests that his charge ride with him throughout the western winter collecting bounties, after which Schultz will help Django find and retrieve Broomhilda, assistance a black man in the pre-Civil War south will surely need. The preceding and following sequences comprise not only the opening ninety minutes of this long movie, but also exist as the purest expression of Tarantino’s affection for the genre to which he’s paying tribute.

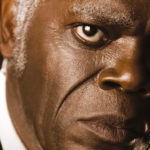

It doesn’t take too long for Django and Schultz to track the damsel in distress to the depraved plantation of ‘Mandingo-fighting’ enthusiast Calvin Candie (Leonardo DeCaprio) and his obsequious house negro, the elderly Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), the movie shifts gears into a semi-tedious Tarantino land of baroque and lengthy scenes of gamesmanship among the characters as Django and Schultz, posing as buyers of Candie’s best and brightest Mandingo fighter, try to trick Candie into instead giving up ‘Hilde’ as she’s called. (Why they couldn’t simply have tried to buy the slave from Candie without all the subterfuge wasn’t clear to me.) Stephen, however, who’s much more canny and watchful than his Stepin Fetchit persona would otherwise suggest, clues his master in on the plot, and all bloodshed breaks loose in a bloody climax full of squibs and fountains and gushers of fake blood better suited to Tarantino’s Grindhouse compatriot Robert Rodriquez’s ridiculous splatter epic Planet Terror than any spaghetti western that I can recall having seen.

Not only did the bloodsplatter pull me out of the picture, so, too, did Tarantino’s clumsy and wildly off-putting mini-narrative that takes place in lieu of what ought to be a more natural and organic denouement. With an entire new set of conflict and circumstances to overcome following the massive shootout, the film feels lumpy and overlong by probably much more than it should. Yes, some of the spaghetti westerns were lengthy affairs, but in trying to extend Django’s journey to a similar temporal scope, Tarantino serves only to water down his message, which to this viewer has considerable heft and insight:

What the movie has to say is that America’s a country that once enslaved human beings as a matter of law, custom, and culture, and furthermore, its films have often been guilty of shying away from the the blood on our culture’s hands not only regarding the inhumane practice of forced slave labor, but also the storm of Native American genocide that began over 500 years ago with the European landing on these shores—oh, wait, the movies did cover that, didn’t they? The good guy cowboys, the nettlesome and warlike Indians. Check. No wonder QT insists that this is a Southern: it’s much more honest than any western made pre-1970 or so.

While my highest praise is reserved for the fact that for much of its running time it’s an entertaining and engaging picture, Django Unchained’s refusal to shy away from the brutality of slavery and cinematic depictions of it—see the sweeping title MISSISSIPPI that appears meant to evoke the opening of Gone With The Wind—makes it an important work of reflective cultural art that is more than the sum of its misshapen parts may at first seem.

About dmac

James D. McCallister is a South Carolina author of novels, short stories, journalism, creative nonfiction and poetry. His neo-Southern Gothic novel series DIXIANA was released in 2019.

A fun, wild ride like only Quentin can provide. Funny, heartbreaking, bloody and profane, I left the theater with a new respect for Don Johnson. You heard me. Good review.