The Night I Prayed to Elvis

Here’s the title story from an upcoming collection of linked stories. It’s more about nostalgia, mood, memory and tone than any deep literary insights or big moments. This material is from much earlier on my writer’s journey, nearly 20 years, and often reads that way.

The Night I Prayed to Elvis

The war with Daddy (and sometimes Mama) over my music makes me so mad I want to cuss. It’s gotten so bad I sometimes spend all night listening to my little radio right next to my ear turned down real real low. It’s the only time I can listen and not get my butt spanked over that “thump-thump-thumping mess on them records of your’n.” Daddy’s old. He don’t know what’s good and what’s not on the radio. He don’t know about records.

When he’s home and I’m playing my KC & the Sunshine Band album, which is one of the few whole albums I have, he gets extra ornery. “How long is that same durn song going to go on?” That always makes me laugh at silly old Daddy: KC & the Sunshine band has a whole bunch of songs, and every one of them is good, but it’s definitely not one long song. Nobody puts out a record that’s one long song. That’s just dumb. “Turn it off,” he finally begs me. “Lord, set me free.”

When he’s home and I’m playing my KC & the Sunshine Band album, which is one of the few whole albums I have, he gets extra ornery. “How long is that same durn song going to go on?” That always makes me laugh at silly old Daddy: KC & the Sunshine band has a whole bunch of songs, and every one of them is good, but it’s definitely not one long song. Nobody puts out a record that’s one long song. That’s just dumb. “Turn it off,” he finally begs me. “Lord, set me free.”

P’shaw, I say.

Daddy might get his drawers in a bunch over by the sound of my music, but Mama’s always more worried about what they’re saying, which I will admit is sometimes hard to understand, especially with the Bee Gees.

“What difference does it make what they’re saying?”

“Because nowadays there ain’t no telling what them people are singing about.”

“Mama, whatever it is, it ain’t nothing bad! They wouldn’t play it on the radio if it was.”

“That’s why they make it so hard to understand—to trick you. Just like ‘Louie, Louie.’ I remember at your Daddy and me’s prom night, the principal made them fellas quit playing when they started that.”

Come to think of it, Mama’s kind of right about that one—I don’t got no idea what they’re saying in ‘Louie, Louie.’ But like I was trying to tell her, if it sounds good and you can dance to it, what difference do a bunch of stupid words make?

Neither of my parents mind when I play one of Mama’s old Beach Boys records, which I didn’t understand until she explained that those songs were the ones that she and Daddy liked when they were first getting together. Maybe that’s why I love the Beach Boys so much. Maybe I could hear that music when I was still inside her tummy. It makes me feel kind of special, what with Mama and Daddy and me all liking the same music. For once.

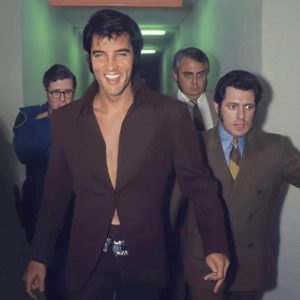

Mama says her favorite singer, though, is still Elvis, “like he was before he went off into the Army.” I can’t hardly believe they made Elvis go into the Army—wasn’t what he did important enough that he could get out of it? That’s all over my head. I reckon the reason is that he had to go and fight in Vietnam like Daddy did with his friends Reynolds Pettus and Buddy Sykes. Daddy and Buddy come home, but Reynolds didn’t. Reynolds was Daddy’s best friend. That’s about the long and short of what Daddy’s got to say about Vietnam—that he took and left his best friend behind, which for a long time I didn’t understand meant that Reynolds got killed there, not just left.

“I didn’t get so much as a scratch, but Rennie,” which is what everyone called Reynolds, “didn’t make it past the second week in the field. Great god almighty,” and then Daddy’s eyes look all red and funny and he don’t want to talk no more about Vietnam. I ought to ask him if they ever seen Elvis when they was overseas, but I reckon if Daddy had he would have told me that before now. Wouldn’t he?

We was talking about Elvis not too long ago: Mama got all excited when she heard on the news that he was going to have a singing over in Columbia, at the big coliseum where we went to the circus that one time when I was little. She got so worked up that she decided we was going to go see him, and then, buster, I can tell you I got all excited, too. Daddy said we couldn’t afford to, though.

We was talking about Elvis not too long ago: Mama got all excited when she heard on the news that he was going to have a singing over in Columbia, at the big coliseum where we went to the circus that one time when I was little. She got so worked up that she decided we was going to go see him, and then, buster, I can tell you I got all excited, too. Daddy said we couldn’t afford to, though.

After that Mama and Daddy had a knock-down drag-out like I ain’t never seen. “You’re still just jealous of him like you used to be,” Mama said, but Daddy said that people like us don’t run around and go to no concerts, and that she better forget about all that mess. Since Daddy butters our bread and all, what could Mama say? That was that.

All of a sudden Mama’s standing out on the porch with her arms akimbo, which means that her stories must be done because that’s when she comes looking to check on me. “Lucy-Loo, I swear to goodness but I’m not going to tell you again about playing in that nasty ditch.”

“I’m not messing around in the ditch—I’m waiting for someone.”

“Who? Timmy?” Timmy being my big stupid brother.

“No one.”

“Well then, who are you talking about?”

I might as well be out with it, but as soon as I open my mouth I feel silly and stupid. “The Beach Boys.”

Mama snorts and folds her arms. “The Beach Boys.”

“Yes,” which I say like I’m real sure of myself and so what? I stick my chin out. “They’re coming to pick me up and take me to their beach concert.”

Mama gets a look on her face like she’s about to both laugh and cry at the same time, the way her face gets when she sits at the table drinking tea, fanning flies and flipping through our baby pictures. “Is that what my little angel thinks? That the Beach Boys are just around that bend?”

I feel like a dumb little first grader. “No.”

Now she’s got her regular old Mama face again, which around her eyes and mouth is kind of tired looking. “Lord have mercy but the stories you tell, young’un. Now get into the house and scrub them hands and feet clean before you catch every disease in the book.”

“Yes ma’am.” I run and jump barefoot up onto the porch. My legs are gray with dust up past my ankles. “Can I play my records till Daddy gets home? Please please,” begging before she has a chance to answer.

“I reckon so. Not loud, now. Mama’s head hurts.”

“Yes ma’am!” I’m so excited that I can’t even decide what song I want to hear first.

“Lord but it’s as hot as the devil’s kitchen out here.” Mama’s looking down the road at the bend like she’s waiting on Daddy, who ought to be getting home from work before too long. “Let’s go back inside, my littlest angel. If the Beach Boys is coming, I better go put my face on. After I get Daddy’s pork chops breaded.”

Monday’s is always pork chop night. Always. That’s the way may Daddy is—real particular about the when and what of it all. In the summer I can’t hardly tell what day it is, except maybe by what Mama is fixing for supper. She has her schedule—for example, Monday is pork chops—because Daddy’s one of them that likes things to stay they way they are. He don’t like surprises much. Says stuff coming out of nowhere, when bad things happen that you ain’t ready for, that there’s what makes life harder than it ought to be.

A bend in the road.

Our house sits up on a flat rise and is set so’s you can to look down the road both ways, but only a little because there’s a curve one way going down into the woods and then another heading back to the main highway. Anything could come down the road from the highway, but from the other direction is only the river, and old men like my Daddy who fish in it. On a dull as dishwater day like this I sometimes stand looking up around that bend, picturing a bus coming around the corner, but not the school bus I sit on with my best friend Darlynn Murtishaw.

On the bus is fun; it’s where we talk about records we hear on Kasey Casem’s American Top 40 and who was on American Bandstand Saturday afternoon, and that takes us over to the schoolhouse. My bus doesn’t go to the school—oh, no. Instead, my pretend bus is like the Partridge Family’s bus, all colorful and happy, but on this bus are a different music group: the Beach Boys, all of them, coming to take me somewhere that’s full of people and fun and songs.

And on this pretend bus, not only can we play the songs we like? But also we can play them as loud as we want?

Maybe the bus is set up so that we can all dance together too, and once we get to the beach there’s going to be a concert and it’s going to be for me. A bus ride to heaven, that’s what that would be. Not for me alone, I reckon, but still mine. When they come, I don’t know if I’ll ask them to go and stop by Darlynn’s house to get her to come with us. She’s eleven. It’s hard to be best friends with someone who’s eleven but when you’re only ten. That’s a big difference. This summer she got her boobies, wears brassieres. She acts too big for her britches. But the boys, they stand in a line to talk to her. She’s more grown up than me.

Maybe the bus is set up so that we can all dance together too, and once we get to the beach there’s going to be a concert and it’s going to be for me. A bus ride to heaven, that’s what that would be. Not for me alone, I reckon, but still mine. When they come, I don’t know if I’ll ask them to go and stop by Darlynn’s house to get her to come with us. She’s eleven. It’s hard to be best friends with someone who’s eleven but when you’re only ten. That’s a big difference. This summer she got her boobies, wears brassieres. She acts too big for her britches. But the boys, they stand in a line to talk to her. She’s more grown up than me.

I go skip-skipping into my room and strike a pose with my pretend microphone: “Thank you, Edgewater County!” I blow kisses to my audience, spin around and then flop down to flip through my singles. I like to mix them up to make a stack of wax as Timmy calls it when you put a bunch of records on at once. The only one I know I don’t want for sure is ‘Nights on Broadway,’ because I swear to goodness but I can’t get that one out of my head. “I’m Your Boogie Man” and “You Make Me Feel Like Dancing” and “Dancing Queen” are ones I can’t seem to get tired of no matter how hard I try, so I pick those and then “Whatcha Gonna Do?” and a couple of others.

And so now I’m the dancing queen in my little room, spinning and twirling and sneaking the volume knob up a little between each song until Mama hollers from in the kitchen for me to turn that racket down. She calls my music a racket, but sometimes I come out of my room and catch her swinging and bobbing a little bit in front of the stove or the sink.

Like right now. “Wha-choo gonna do when she says good-bye, wha-choo gonna do when she is gone?” and sure enough she’s shaking her tail feather. But only a little. And only, I reckon, because she’s by herself. It’s weird how Mama and Daddy don’t never listen to music ’cept when we go to church, and buster I can tell you church music don’t sound nothing like they play on the radio. Nothing like Pablo Cruise.

I dance my way into the kitchen and give Mama a start, making her jump. “Lord have mercy—Lucy, you liked to give me a coronary.” She goes back to breading Daddy’s pork chops, tossing one onto the cutting board in puffs of flour that go up poof in little clouds.

“Sorry, Mama.” I dance my way around the kitchen table, singing along. “But this is my favorite.”

“Oh, you say that about every durn one—go turn that down, now.”

“You like this one, don’t you, Mama?”

“Oh, I do not. I can’t hardly understand a blessed thing they saying.”

“This’s Pablo Cruise,” not that she’s asked for this fact. “This is my favorite.”

“Oh, p’shaw. What makes him so different that now he’s your favorite?” Now quieter, more to herself than me, scoffing. “Like that ain’t one of them made up names—ain’t nobody never been named Cruise.”

“It’s not a he,” rolling my eyes to the heavens. “They’re a group, like the Bee Gees or the Bay City Rollers.”

“Do what now?” Now she’s humming along, but not really; she’s humming some other tune, like she’s swimming against the tide of my song. “He’s got himself a group?”

“Lord have mercy, Mama, it’s not a he.” Now the song’s fading out. I’m kind of glad, because Mama’s acting like a durn fool, like her mind’s a million miles away. “Pablo Cruise ain’t nobody’s name. God.”

“Hush your mouth, girl.” She cuts her eyes over the shoulder of her housedress. “You think your Daddy’s the only one around here that’ll smack a smart mouth?”

“Yes ma’am. I mean, no ma’am.” The house is now quiet but for the squeak-squeak of the window unit. Where’s my next song? “But Pablo Cruise is a group not a singer by hisself—it’s like . . .”

“Lucy. You think I just wandered in out of a turnip patch?” She’s laughing. “Like I don’t know what a group is.”

“—like the Beach Boys.”

“Yes, sissy. Like the Beach Boys.” She tilts her head at me all funny. “Now look here, I want to tell you something.” She scratches her cheek and leaves a little line of flour like the track of a tear. She’s got a weird look on her face, like I’m about to get me a lecture about something I done wrong. “Don’t stand out there by the side of the road waiting for somebody to come and get you.”

I’m embarrassed again. My voice is so tiny that I can barely hear it over the air conditioner. “Mama—I know the Beach Boys ain’t coming. It’s pretend? Up in my head? Like a story.”

“Angel—I understand that. But what I mean is that you can’t sit on your butt waiting for everything in life to come your way. Sometimes if you want something, you got to go on and get it rather than waiting for it to come to you. You understand, sweetheart?”

“Like when you want to go and get groceries from the store?”

“No. I’m trying to say to you that if you wait long enough in the same spot, you might get stuck there waiting and never . . .” She sighs like she’s tired. “Nothing, Lucy. Your Mama’s just running off at the mouth. I was not going to live my mother’s life. Oh no. And I did not, not for a long time. But here I am. Mercy. Mercy. Here I am.”

“Okay.” I don’t got a clue what she’s going on about, but she’s all distracted and just standing there, looking at that pile of dusty pig meat waiting for the grease, and I’ll be durn if she don’t curse a little under her breath, rinse her hands off, and go back onto the porch smoking one of Daddy’s cigarettes. I ain’t seen her do that since Uncle Junior got killed, bless his soul.

I run back into my room to find my record turning around and around, skipping right at the very end of the music when you can barely hear anything. I pick up the needle and pull it back, letting the next record fall.

Supper’s good, but Daddy is a crab-cake, all grouchy and tired and hot. Timmy’s not here tonight, and like I said, nothing burns Daddy up more than everyone not being at the supper table.

“Where’s that boy of mine?”

“He’s over at the Waughs playing touch football and then taking supper with them,” Mama says as she gets up to refill Daddy’s sweet tea for him. “Or so he says.”

“I’m going to whup that little cuss but good.” Daddy smacks his lips like he tasted something bad. But he didn’t—after he cuts into his pork chops, which are so tender he only has to use his fork, he goes Mm-mm. “That boy’s missing out on a fine meal that his Mama spent all afternoon fixing. That ain’t right.”

I don’t see what the big durn deal is. “Maybe he’s tired of eating pork chops on Mondays.”

“Do what?”

“I said, maybe he’s tired—”

He drops his voice. “Now hush up, Lucy, before you hurt your mama’s feelings.” He gestures with his fork toward my plate, where I’m pushing peas around. “Eat like you appreciate what you got in front of you, now.”

“Yes, sir.”

Mama comes back with his tea, and then the rest of the meal is us sitting and eating with the sound of our forks and knives going squeak on the plates, and also the squeak-squeak of the window unit, of course. But right about the time Mama gets set back down good and picks up her fork, we hear this godawful racket from out on the back porch where the washer sits: THUMPA-THUMPA-THUMPA. It’s off-balanced again, which happens all the time. Mama fusses and scolds about need a new machine.

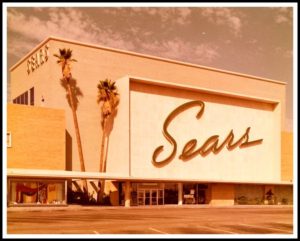

Daddy drinks his tea and as he’s swallowing his big Adam’s apple bobs up and down. “Maybe we’ll run over to the Sears one day soon and take us a look. I sure can’t see putting no more money into that thing,” which is the same thing Daddy said last year when he wanted a new truck. “It’s bout wore plumb out.”

“One day, one day soon,” Mama says in a voice like she’s mocking Daddy. “It’s always ‘one day soon’ with you.”

Daddy pokes out his lips. “I’ll have you know I resent that, Mother.”

Mama looks like she bit into a persimmon or a sourball. She gets up and shuffles through the kitchen toward the back porch, mumbling and grumbling.

“Sissy,” he says. “Look here: You want to ride over to the Sears tomorrow?”

“To Columbia?” Once in a blue moon we ride over there, usually on Saturdays, but I can’t ever remember going on a Tuesday. “Tomorrow?”

“You know what? Let’s take your Mama appliance shopping tomorrow afternoon. I get off at three. If the truck’s early, maybe by 2:30.”

Oh my goodness gracious—and what else do they have at Sears besides washers and everything else under the sun? Records. Lots of them. I’ve been saving nickels and dimes all summer in a jar under my bed, I think I almost have enough to buy a whole album again. I got my KC and the Sunshine Band from Santa Claus last year, but if I have to wait until Christmas to get another album, I’m liable to bust. I explode with an excitement, yes yes yes to this idea, Daddy.

“Settle down now,” he says. “I ain’t never seen anyone get so excited by the notion of going washing machine-hunting. Must be because you ain’t the one what’s got to pay for it,” which cracks him up like when Jerry Clower’s on Hee-Haw.

When Mama comes back to the table and he says to her what we’re going to do tomorrow, she doesn’t get half as excited as me even though she’s the one who wants the durn washer in the first place: A question, but she don’t put it like one. “Will wonders never cease,” is all she says.

“All right now,” Daddy says, scolding. “In everything give thanks, for this is the will of God.”

Now, Mama’s in church every Wednesday night and twice on Sunday, but something about Daddy quoting the Bible sets her off. At first she don’t say anything, but I can see on her face that she’s ticked off. I think I understand why— most Sunday mornings she’s got to half drag him to church, because he’d rather set outside on the porch and look at the paper. Finally she says, “Unto thee, O God, do we give thanks, unto thee do we give thanks: for that thy name is near thy wondrous works declare.”

I swear to goodness but I think she’s being all smarty-pants. She’s looking right smack at Daddy instead of having her eyes closed or else looking up to the Lord in His heaven.

Daddy’s chewing and smacking. “I tell y’all what—this here’s some good eating, Mother. Bless your heart for everything you do.”

I barely hear them—all I can see are about a hundred different album covers all spinning around in my mind, like when I run across one of them record club ads in Mama’s magazines. I keep begging to let me get the six records for only a dollar (or sometimes a penny!) but Mama keeps insisting that it ain’t nothing but some trick for getting a whole mess of money out of you sometime later. No matter what’s to come tomorrow, the rest of my supper tastes extra good.

“Once Daddy gets home, you’d best be ready to go,” Mama says from my doorway the next afternoon. She’s gone and put on makeup, and also changed into going-to-town clothes, which fall somewhere between house clothes and church clothes—a decent and proper dress, but nothing fancy, sandals and no stockings. “We don’t want to dawdle.”

“Once Daddy gets home, you’d best be ready to go,” Mama says from my doorway the next afternoon. She’s gone and put on makeup, and also changed into going-to-town clothes, which fall somewhere between house clothes and church clothes—a decent and proper dress, but nothing fancy, sandals and no stockings. “We don’t want to dawdle.”

“We won’t.”

“All right now young lady, I’m serious.”

I don’t know why she’s worried—I never wanted to go nowhere more than I do that Sears. All I been thinking about all day is them records they got over yonder. “Yes ma’am. I just need to brush my hair and put my money in my pocketbook.”

Daddy comes in and dumps his keys and change on the table, plops down heavy in his chair, kicks up the footrest and sighs. He has to go in to the grocery store real early on Tuesdays because that’s when one of the big trucks comes. He’s important—he’s the produce man.

“I’m wore slap out.” He goes on to roll his eyes and talk about The Wheels having been there today. You’d think he meant the big truck, but what he really means are the big wheels—the grocery store is one of them that’s in every town, and The Wheels are the men from the district office. “Them puffed up jaybirds were looking cockeyed at everything today. Great god almighty. One of them took out a white glove and started running his finger every which way. Like we don’t keep no clean store.”

Mama, who hears this same speech every time The Wheels come around, squints hard-eyed and suspicious at Daddy. “Well—ain’t we going?”

“Do what now? Going where?”

“Don’t you want to get on over yonder before that five o’clock traffic hits?”

“Over where?”

“Lord help,” Mama says. “I should’ve known.”

Daddy picks up yesterday’s Edgewater Advocate and fans himself. “Go where now?”

I can’t help myself. My whole head is hot. “To the Sears to get Mama a warshing machine!”

He rubs his temples like he’s tired, but his eyes look all twinkly. “Oh, but I’m so tired my legs are tingling. We got in coconuts and pineapples today, girls. Big old crates of them. If y’all will let me nap for an hour or two . . .”

Mama’s eyes roll back in her head like that crippled girl at school. Her mouth is set in that upside down smile she gets when she’s mad about something, but don’t want to say what she’s on about. But this time she up and does: “I knew you were all talk yesterday. Knew it just as sure as I’m standing here.”

Daddy’s got a funny little smile. He slams the footrest down and goes into the bedroom, shuffling his feet like the tiredest man in Edgewater County.

I feel like I’m going to cry. “Oh, let’s just go on without him. Please?”

She scoffs and p’shaws. “I can’t stand driving with that bunch of crazies over there.”

“But Mama—”

“Besides, sugar, I can’t go and buy nothing without Daddy.”

“Why not?”

“You’ll understand one day.”

Right then Daddy comes busting back out of the bedroom, and ta-da, he’s done changed out of his work clothes. I can smell that he’s put on a fresh coat of his Old Spice. That old rascal.

He claps his hands together. “You got your checkbook, Mother? We’re a-gonna need it.”

Mama’s mouth is hanging open like one of them crappie that Daddy and Grandy catch when they go fishing up by the dam. “You turd.”

Now Mama and Daddy start laughing. She goes and gives him a little kiss; he squeezes her rump, which he only does when they are both happy.

I run to get my jar of change.

When I come back out Daddy’s drinking himself a Fresca, which he likes better than them Co-colas and RC Colas which, he says, give him thick nasty spit at the back of his throat.

He asks Mama, “Where’s my firstborn? I know he don’t want to miss out on a ride over to the city.”

Mama’s fussing around getting her pocketbook together. “He took and rode over to the state park to go swimming.”

“With who?”

“With that bunch he runs with.”

Daddy looks all pinch-faced like Mama did when she thought we wasn’t going to get the washer. “He’ll probably have more fun doing that anyway, I reckon. All right now, let’s get ourselves road-bound. It’s a helluva,” catching himself before Mama can say You better hush that filthy mouth Travis Latham, “I mean, heckuva drive all the way over yonder.”

“Oh, fiddlesticks. It ain’t but a half hour. You drove twice that far to go to Hartsville with Hill Hampton and look at the car auction, and we wasn’t even looking to buy nothing.”

“I was too,” holding the door open for Mama. “I just didn’t find nothing I liked.”

“P’shaw.” But not like when she’s calling bullcrud on something—she’s got a cutesy little smile and he does too, the both of them looking at each other direct into the eyes. “Now, can we go, please, Mr. Latham?”

“I don’t see why not.”

Pulling into the Sears parking lot there’s a mess of other cars, which makes Daddy ask what in tarnation all these people are doing out shopping on a regular old Tuesday. Mama and Daddy both can’t stand crowds and standing in line, not even at the Sideboard Steakhouse in Tillman Falls, but I think it’s worth it cause they got one of them hot food bars now, with macaroni and cheese and Swedish meatballs and a section full of cakes and pies.

Pulling into the Sears parking lot there’s a mess of other cars, which makes Daddy ask what in tarnation all these people are doing out shopping on a regular old Tuesday. Mama and Daddy both can’t stand crowds and standing in line, not even at the Sideboard Steakhouse in Tillman Falls, but I think it’s worth it cause they got one of them hot food bars now, with macaroni and cheese and Swedish meatballs and a section full of cakes and pies.

If Mama hadn’t wanted a new washer so bad I reckon she wouldn’t of wanted to come over here at all— the whole drive she sat with her shoulders up around her ears, holding onto the dashboard whenever a big truck blew past us. Mama grew up out in the country, right where we live now. She says she didn’t get very far in life, only down the road a piece from Grammy and Grandy’s house. So maybe that’s why she don’t like the city much. I don’t know that Daddy does either, and I reckon we could’ve gotten ourselves a washer over in Tillman Falls, but Daddy says there’s deals to be had at a big store like Sears.

And what a big store this is! We go in through the sliding doors, whoosh, and then there’s everything a body could ever want or need, if you got enough nickels and dimes and quarters.

I wish I could live in the Sears or the K-Mart—you’d never have to leave except maybe to run out to the grocery store, but them are never far away, sometimes in the same plaza as the other big stores. If I had all them records sitting there waiting for me to play them, I don’t think I’d even remember to eat anyway. I could pick out pretty clothes right off the rack, lay on one of them new mattresses they got, get cold drinks out of the machine over in the little area that’s near customer service, and then dance my way to the records and start flipping through until I find the one I want to play—a different one every night, as loud as I want. Loud enough to feel the words and the music in my bones.

Lucky for me the washers and dryers are right near the TVs and radios, which are right near the racks of records, so Mama says I can go over there by myself while they shop, which makes me so glad—normally she likes to keep me close at hand, but dang if I’m not almost a 6th grader at the middle school, and that makes me almost this close to being a teenager like Timmy. So, I go dilly-bopping my way down the rows of washers, past the stereo sets and the wall of TVs, a dancing queen in her castle.

A little knot of people are standing at the TVs, shuffling around with their arms folded. The TVs are all on the same channel, the sight of which always makes my head feel funny like that time when I was little and Mama took me and Timmy to the picture show in Tillman Falls to see The Aristocats and we set way too close to the screen? And after a big closeup of Duchess with her white fur and sparkling eyes I got sick to my stomach and then we didn’t get to see the end of the movie? Dizzy, like.

People are hubbubing and shaking their heads. A woman is dabbing at her eyes. Her husband says to another man, “Well, this just beats all I ever heard.”

The man, about my daddy’s age, sucks his teeth and says, “It’s like, dang. The King.” He blinks his eyes and his cheeks get red and then he goes and walks away fast.

A man with a Sears name tag on his short-sleeve plaid shirt says, “Well, this must be some kind of tragedy. A tragedy.”

“Mister, why’s Elvis on them TVs?”

The man who works there says, “They saying that he died, honey. I don’t half believe it . . . but there it is.”

“Elvis?” My stomach feels like it does when you go over the rolly-coaster at the State Fair. I can’t hardly find my voice. “Do what?”

The woman breaks down sobbing now like Daddy does when we go out to the cemetery for him to see the gravestone of his friend who didn’t come back from the war. He don’t know that I know he cries like that because he makes me wait in the truck. Crying like that is something you supposed to do by yourself, I reckon, which makes me scared to see this woman crying like she done started doing right here in the middle of the Sears.

Something snaps inside my head: I got to go and get Mama.

I run back past the stereos toward the machines. Mama is lifting up lids while Daddy and another man with a Sears name tag stand talking with their hands on their hips like Daddy done when he went to Hill Hampton Motors to get his truck last year. I start hollering at the top of my lungs to get their attention.

Mama turns white as one of our bedsheets. “Lucy, what’s wrong?”

“Mama—Elvis died.”

Her eyes get all big, dart over toward the salesman. “Oh, sissy, now hush up with your stories. That’s ugly to say about someone. Especially Elvis.”

“No,” the Sears man says. “She’s right. Heard it on the radio, right before I walked over to help y’all.”

“Elvis Presley?” Daddy says, like there could be anybody else in the world named Elvis.

“Hell of a thing,” the salesman says. “Heck, I mean.”

Mama’s got a funny look on her face like the time the man come to tell us how much it was going to be to put a new roof on the house. “Where’d y’all hear that mess?”

I grab her by the hand, hustle her over to the TVs. Mama’s hand in mine is clammy and cold. We stand there looking at the 5 o’clock news, which ain’t even about Elvis no more. “Lucy you’d best quit messing around with me today,” and she says it all mad but I swear to her that I ain’t messing with anybody.

The other Sears man is still standing there in his short sleeved shirt and tie and name tag. “Help y’all with anything?”

She asks him about Elvis. He shakes his head sadly. Mama about keels over.

“Watch yourself there, ma’am.” The Sears man takes her by the elbow and leads her over to a Lay-Z-Boy they got sitting in front of the TVs, so’s you can see how it feels to sit and look at them, I reckon.

“What happened? Did he get killed in a car wreck?”

The man tells us that they don’t know yet, but that it might be a heart attack or stroke. And then he goes off to talk to a man fiddling around with a console TV, one that has a stereo built inside.

“Mama—I can’t believe it,” with my voice all shaky.

“I still don’t believe it.”

“But it was on the TV earlier.”

“I know, sissy. I believe you . . . here,” pulling herself back up like when she’s real creaky and tired and still has the kitchen to clean up. “Let’s go look at your records.”

The crying woman from earlier is on the record aisle. She looks half crazy, her eyes all red and wide. Her husband has a stack of albums in his arms. “They don’t got poop for Elvis records in this damn store,” she says, her voice all harsh and angry.

Oh no—I had decided to get an Elvis album! I have that feeling like when I caught my cousin from North Carolina stealing money out Mama’s pocketbook that one Thanksgiving—like something personal has been done to me and to me alone. The plastic separator that says ELVIS is flat against the one in front of it that says ELO which is for Electric Light Orchestra. “Mama, she done took every one.”

“You’re damn right,” the woman says with a mean cut on her voice. She makes a HAH sound and then drags her husband off, hurrying on toward the checkout stand with her stolen Elvis records. “These is going to be worth a lot of money now.”

Mama goes right over to where there standing and starts flipping through the records. She cuts her eyes at the woman’s back, but they’ve down hightailed on their thieving way.

Mama looks mad enough to bite a rock in half. “Well, I’ll be shit. That painted-up hussy took every last one.”

I ain’t never heard my Mama use a bad word like that. Now I feel like I’m going to cry. And I do—I start blubbering, sucking breath. “Mama, I can’t believe that Elvis is dead.”

“Well, darling.” She pulls me to her. “Just pick you out something else you want and Daddy’ll get it for you.”

“Okay,” sniffling. “I reckon.”

Mama lets me go and wanders off, hugging herself like she’s cold.

I can’t hardly think straight now. All I can think about is Elvis and the fact that that crazywoman took all his records. I start flipping through looking but I can’t find nothing I want. Not until I find something special that’s stuck in the wrong place, something that makes me catch my breath like I seen a ghost:

Elvis—there he is, in a shiny gold suit. A big picture and then a bunch of little ones, the same one, repeated all over the white album cover. 50 Million Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong. I get chicken skin over my whole body.

“Mama.” My voice screeches and my throat hurts. “Come back quick!”

Both Mama and Daddy are already running my way. Daddy looks scared. “Sissy, now what is it…?”

“Look yonder.”

Mama’s scared face melts away when she sees the record. He takes the album out of my hand, says to her, “You used to have this one, didn’t you, honey?”

“I did.” Mama takes the album and holds the cardboard cover to her body. “I don’t know what happened to that thing.”

“I think we threw it out that time when Timmy was a squirt and took a screwdriver to all them records that used to sit under the coffee table. Here: let me get it for you.”

“In honor of the King,” the salesman says. “I bet them things is gonna be worth some money now.”

“Oh,” Mama says, her mouth downturned. “We don’t need to buy some stupid old record.”

“P’shaw,” Daddy says, taking Mama’s favorite word right out of her mouth and making it his own. “And you, pudding-pie—you go and get you one, too.”

“But Daddy, ain’t no more Elvis records but the one.”

“Get some of your music. Besides, I ain’t never seen you play a Elvis record in your life.”

“I shouldn’t buy no one else’s record. Not today.”

“Go on, now.”

As I run back to the records, I hear Daddy say to Mama, “I don’t think they’s too many good deals here. Let’s just run over to Mr. Vincent’s tomorrow or the next day. Keep our money in Edgewater County.” If Mama’s got anything cross to say about not getting her new machine, I don’t hear about it. I look back to see them hugging, and it looks like Mama is crying, finally, which makes me feel bad for her.

I flip through the albums until I feel like I’m going crazy. Everybody’s buying that Fleetwood Mac thing but I don’t like it that much, leastways not what I keep hearing on the radio? And I don’t like that picture of them two people on the cover, something about it seems weird? Andy Gibb, though, now there’s someone I love. I love that one song of his that they been playing all summer, so I bet all the other ones he has are good too, and so I pick that one. Andy Gibb’s album cover, now, there ain’t nothing weird about a picture of somebody who’s that handsome. He looks like a dream, an angel with his white teeth and tan skin and shiny hair.

Daddy buys the records and we go home, stopping by the Burger King and eating and then riding again in silence but for Paul Harvey on the radio, talking about Elvis.

When we get home, Daddy yells at Timmy for having his music too loud, Mama goes in and puts on the TV and looks at the national news, which is all about Elvis, and she dabs her eyes all the way through eating the supper we brung home from the Burger Chef out on the highway. We sit there eating and not talking about nothing, which is how Daddy usually wants it.

Timmy spoke up with that smart-alecky voice he always uses since he turned into a teenager. “Elvis looked all fat and sweaty in them pitchers they showed of him.”

“Timmy,” Daddy said, putting his fork down. “Shut that smart mouth of yourn.”

I go brush my teeth and get ready to say my prayers. It don’t feel right doing it, but when I pray, I’m praying to Elvis, who has now gone home to his father’s many mansions in the sky:

“Elvis: I know you are trying out your angel wings right now but I want to pray that if you could could you please ask Jesus to make my Mama feel better. I think she misses you something awful. I can’t half believe you are gone but if they say on the TV that you are, then I reckon you are. I’m sorry. Amen.”

I feel naughty somehow, but not silly like when I’m wishing for the Beach Boys to come around the bend to get me. Elvis can hear me now, unlike the Beach Boys, so that makes it not silly at all, not so long as Jesus don’t mind that I talked to Elvis instead of him tonight.

As everyone else toddles off to bed, the house gets quiet. Mama came by earlier and stuck her head in saying goodnight. I didn’t say anything back—I laid here pretending I was already asleep. I don’t know why I did, other than the fact that I keep feeling sad and lonesome.

Maybe I’m sad because summer’s almost over. Before you know it, school will start and next the State Fair will going on and then Thanksgiving and then Christmas will come, and then the New Year, which, come to think of it, is another time Mama always acts sad. Last year when we was watching the ball drop on TV—it’s the one night I get to stay up as late as I want because she always says there’s only one New Year’s Eve a year, and in its own way it’s as special a day as Christmas or Easter—Mama said to me that if you take a notion, New Year’s is a time when you can start over and fix whatever didn’t go right in the old year.

I sure didn’t know that Elvis was going to die this year, but as far as I can tell, dying is something that nobody can fix. But I reckon he didn’t expect to either. No one ever does; when you die, I reckon it just kind of happens, like with my grandmama a few years ago. But that’s a long way off for me. There ain’t no need to worry about going to heaven, not when you are ten years old and about to start the 6th grade.

—end—

About dmac

James D. McCallister is a South Carolina author of novels, short stories, journalism, creative nonfiction and poetry. His neo-Southern Gothic novel series DIXIANA was released in 2019.

DMAC, re “ The Night I Prayed to Elvis” trying to ‘read’ the mind of a writer, was this a Life turned Fiction Short Story? If so, grateful for a dialogue on receiving the news on Elvis death in the TV section of SEARS? If that’s how it really happened, all good – but if that’s writer’s choice, keen to know more about that choice? Grateful – regards, Shmitty

Well… like all my fiction, it is a hybrid of a real memory (Jenn being at Sears on the day Elvis died and seeing his face on all the TV screens) and the specific narrative needs of my Edgewater County mythos, as well the linked collection of which this story is a ‘chapter’. For instance, the father character has a crucial but minor part to play in my Dixiana series, having to do with his service in Vietnam and the friend he left behind (the father of the Dixiana protagonist). Everything but the central image that inspired this Elvis story—well, and the little girl’s love of the Beach Boys and her fantasy about them coming to get her—can be considered fictional.

Bear in mind that all fiction is autobiographical in some way. It just might be well disguised, which of course is not the case here.