Letter to a Dead Girl

Dear Allyson:

It’s that grim anniversary again. I was up before the dawn today thinking of you, and of how there are no more dawns and dusks where you are, which is not with us here on the blue rock.

I remember everything so dreadfully well on that day thirty-two years ago, much longer than you ever got to live. How much longer did you have to go before you got your degree? And what would it have been? Early education? Did you want to be a teacher? That sounds right. A dean’s list scholar.

I kept your school books, and often read the big red Shakespeare text—I can see it sitting on the shelf out of the corner of my eye right now. This passage from The Tempest sticks to my ribs:

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

Many small details of your life—but not who you were—have long begun to slip away.

Others, I carry with me.

I carry your heart, as e.e. cummings wrote. It takes discipline—what did your voice sound like? What was it like to hold your hand, to watch you walk toward me, smiling and happy, to see each other for a brief moment between classes on the university campus? To sit across and watch you eat? To kiss you, to make love with you, my first lover, my fiancée, my angel? Some details swirl unforgettable in my consciousness.

What did we talk about when we were together? If only I could remember. We’d been a couple “a long time” at that point—only five years, but at the tender age of 21, a small eternity. I can only say this much: we did know one another. We were like an old married couple. We’d even had a breakup or two, infidelities.

Xmas 1986, showing off the ring.

Well—on my part, at least, not that you ever knew. Meaningless, drunken encounters that left me guilty and ashamed of myself. You went on a couple of dates with guys in 1985, during that period after you told me in front of the Humanities building that you didn’t want to be a couple anymore owing to my selfishness, my inattentiveness, my partying with my boys’ club. I don’t know what you did on the dates or who they were. It doesn’t matter. I would get you back, as you got me back when I did the same to you about a year later, a piffle of a breakup that led to me buying you an engagement ring.

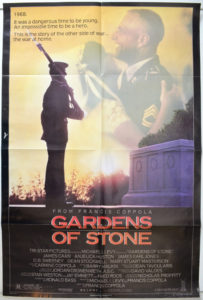

The folds in the poster remind me of the ones I used to collect, that you bought for me as holiday and birthday gifts. I still have them.

What was the last movie we saw? The Secret of My Success, horrendous, a mainstream, silly Michael J. Fox comedy vehicle, I think the Friday before you died. On the night of May 10, we had planned to come back home to Columbia in time to catch Gardens of Stone at the nice downtown Jefferson Square cinema. A Francis Coppola adaptation of a novel I’d read, I didn’t see it, not since I ended up in a hospital bed that night. I watched it years later, finally, and wept through the whole movie thinking about you, and what might have been.

Ah, the movies.

I was working once again at the Cinemas, my second go-around there. I’d gone back to the theaters mainly because it was a job I knew and I had left on good terms. I was looking forward to the summer movies. The trailers looked good for things like DePalma’s The Untouchables and the adaptation of Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick—that was the one you were looking forward to the most. I remember when you came to pick me up from work one day, and I took you into one of the features just so you could watch the trailer.

Nicholson, Cher, a visual director in George Miller—Wow, you said. That looks great!

Later in the summer, I don’t remember the movie being good. They can’t all live up to their trailers. Somehow I was glad.

I remember all too well going to those films without you for the rest of the season, sitting numb in the dark—my religious experience at the time, the only one I knew—and broken with disbelief, denial, vivid PTSD that has never quite left me. I’d never minded going to the movies alone, not until after you were gone. I would recall an incidence of precognition I suffered one evening while we were sitting in a theater waiting for the lights to go down—I looked at the side of your face in gentle, pleasant repose, holding your warm hand in mine, but feeling the cold rush of fear at a thought:

She will be gone.

Hi there, gorgeous.

Those were the little words that rang out in my head. A gush of fear—it made no sense. We were young. She wasn’t going anywhere.

It wasn’t the only premonition like that. A dream of a car accident, specifically a little red station wagon you used to drive, seems now to have been another psychic marker that tragedy lurked in the future. I can’t explain it, or maybe I can, but that is another discussion, and useless here anyway because where you are, you have all the answers.

Remember that day? I do.

The evening before the nightmare that would be Mother’s Day 1987—we were going home to Lugoff not just to see my mother, but so that you could put flowers on your own mother’s grave, Willie, who had died suddenly while we were still in high school—we held a gathering of some of my Media Arts friends in the new apartment we’d leased together. Doug, L.C., Sabrina, Cary, and your fifteen year old brother Jack: a goof, a ladies’ man, a decent kid who loved hanging out with us older folks in the “big” city.

We sat on folding lawn chairs in the living room of our apartment on Sims Avenue, the one we’d taken in order to get our real lives started together, away from the dorm scene and easing out of college altogether, at least for me. I don’t remember anything of note about that night, about what we discussed or jokes we told or stories LC might have laid on us from his days gigging as a professional musician—he was older than the rest of us, a forty year-old man amongst college kids, who would drink himself to suicide ten years later. But at the time we were all close friends. I’m sure we talked about Media Arts stuff. We probably talked movies. Drank beer. Smoked, cigarettes and otherwise.

I should remember the evening better—I didn’t even drink that much. I was cutting back on all that. I was about to make a film that fall, the first of many dreams I hoped to accomplish, and to write my second screenplay. Life beckoned.

Most of all? We were growing up.

The morning of the accident, we woke up in the quiet and still, with sunlight streaming in through the windows of the old apartment building. We made love—quiet, gentle, so as not to let Jack hear us. It was over quick, too quick. I will never forget your sly look—I would make it up to you later that night.

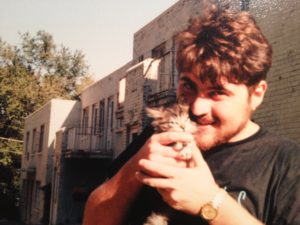

We yawned and stretched and lay in repose for a few minutes, but it was time to get up. We needed to feed Alvy, the cat you’d brought home from the shelter earlier that year, and also Max, our new kitten, maybe ten weeks old, another rescue. Alvy was my baby; she’d lived in the University Terrace dorm with me because you had no way to conceal her across the street in the busy South Tower building. UT was an apartment, not a dorm. I’d been lucky getting in there—I never had to tough it out in the “honeycombs” or other regular college dorms, and the best part? Alvy was able to live with me. After loving many animals in my childhood, she became the first pet that I could call my own.

We yawned and stretched and lay in repose for a few minutes, but it was time to get up. We needed to feed Alvy, the cat you’d brought home from the shelter earlier that year, and also Max, our new kitten, maybe ten weeks old, another rescue. Alvy was my baby; she’d lived in the University Terrace dorm with me because you had no way to conceal her across the street in the busy South Tower building. UT was an apartment, not a dorm. I’d been lucky getting in there—I never had to tough it out in the “honeycombs” or other regular college dorms, and the best part? Alvy was able to live with me. After loving many animals in my childhood, she became the first pet that I could call my own.

Now eleven in the morning, I suggested to Jack that we split a cold beer for the road. Not take it with is, just drink one real quick. We did that. It was fine. I drank all the time—one beer was nothing. It would be a long day of visiting family. I wouldn’t have another for many hours. I drank far too much in those days—a true teenage alcoholic. One beer to me was like a glass of milk to most people.

I can close my eyes and remember this moment, outside the old dorms holding my kitten. You took this picture.

We piled into the car, a mustard-yellow Mustang my grandfather, a used car dealer, had gotten for me after my Datsun gave up the ghost. We brought the cats with us; we wanted my mother to meet Max, and for her to get to see Alvy, with whom she’d fallen in love like she did with most animals, rest her blessed soul.

The car seemed full: A hanging basket (a fern?) for my mother, other objects, three humans, two cats. I don’t know if we had the flowers yet for your mother’s grave out in the rural countryside of Kershaw County, beside which you are now buried. The road from Columbia to Lugoff, a major interstate highway, was busy. It was Mother’s Day, all the children traveling to pay tribute to the women who had borne them.

Laughing, talking, listening to music, we passed by the Alpine Road exit. I don’t know what song was playing, probably the radio. We discussed the coming week—how we needed to buy some groceries, but didn’t have much money. You were waitressing, working for tips. One of the managers at the restaurant said he was going to open his own place, that he wanted to bring you on as the head waitress, pay you a better hourly wage. Money or not, our near-future life together seemed settled.

We were happy. We had the rest of our lives to worry about money. “I’ve got 10 dollars tucked away,” you said, cheerful, don’t-worry. “We can get a few things with that.”

I put on my blinker to pass another car. Jack said something. Maybe I glanced back him; maybe I answered.

“Donnie!” This, the last thing you said—a shriek. That name is what people from childhood and high school called me, or still call me to this day. A college man, I had transformed by then into “Don”—Donnie was a child’s name. I wasn’t Donnie anymore.

And then? “Donnie” died for real, or at least the idea of him: the last vestiges of any reasonable sense of childhood innocence, swept away in an instant.

The black spot they talk about experiencing during accidents like this. A blankness.

A sensation of flying.

A sound like HUH—your death rattle. I didn’t realize this for a long time.

And it was as though I opened my eyes from a dream, but into a nightmare. The shattered dashboard was my first perception. Something terrible had happened.

I heard a sound from behind. Jack, bloodied and twisted into the wreckage, whimpering in pain.

I glanced at you. Your face was pale. The engine block, steaming, was in your lap. The smell of gas and oil. I looked back. Jack, twisted in the metal, his eyes open, his face a bloody mask. Are you all right? It was the most absurd question ever asked in the history of language.

Alvy. There, my cat, lying on her back, alive. I pulled metal away from her, held her to me. She growled. (Her leg was broken, but I didn’t know it.)

I looked over at you. You were dead.

I was screaming, now, at the cruel realization of what had happened. I looked to them.

Onlookers starting coming up, gazing into the wreckage.

What happened? I don’t remember what anyone said in response.

Oh please help us. Please get us out of here.

Just sit still, son.

I don’t remember their faces. The clearest image I have is of an old woman coming up, looking inside. I looked at her, made eye contact. I didn’t say anything. She walked away. She was just a gawker, gazing in on the bloody tragedy.

I begged again. Get us out of here. I meant all of us—you, Jack, Alvy.

I didn’t know where Max was. I never saw him again. Later, someone told me that they had lain him by the side of the road. He had died, my new little kitten. We had saved him from the shelter, only to die anyway.

A man reached in and took Alvy from me.

I know Alvy awaits me on the other side of the Rainbow Bridge.

Oh please, don’t take her, I wept.

Just give me the cat, son. She’ll be all right.

I did. That was when I began crying, screaming some more. My vision blurred; I thought I was dying, too. I was glad. But it turned out to be only blood, my own, running down into my eyes from a gash across my forehead.

I pled to God, now:

Don’t let me die, too. It’s too soon—it can’t be over yet. Please.

And here I remain.

Responding to my earthly entreaties for help, men began yanking at what remained of the driver’s side door. My seat was the only part of the vehicle not crushed, misshapen. At last they pulled off the door. I started to get up and out of the car, no different, in a way, than anyone does after they’ve arrived somewhere and shut off the motor and ready to go on about their earthly business.

No no, don’t get out. Sit still, someone said.

Oh please, no. Let me out.

Don’t get up, another voice said, a hand gently pushing me back down. You’re hurt.

I was helpless. I had to do what they said. I waited, there in the seat, the ruined car all around me, Jack moaning and begging, my cat gone and you dead beside me. That’s what we were working with for a long time.

The Guardian of Forever from Star Trek. If I could get there, I would wait until May 9, 1987 came around, I would jump in, and we would never have gotten in the car that day.

The minutes unfolded. I was aware, awake, alive. I kept turning to look at you, until I made myself stop. Your face, so pale, your lips turning purple. Crushed by an engine block, you nonetheless seemed at peace, those same lips slightly parted, your eyes droopy but open. You weren’t in pain, didn’t seem to have been in agony. You died instantly, they said. Later, when my mother came into the emergency room, I said, Oh, she was still alive for a few seconds, I think. But you weren’t. I don’t know why I said it. I didn’t really believe it.

The EMTs and police arrived. A young man, the sweat rolling down his face, looked in from your side. He reached in and put his fingers on your neck, feeling for the pulse.

I already knew, but I asked anyway. Is she—?

Yeah. She’s gone, pardner.

Okay, I replied. Okay.

The details from this point are important, and yet not. No more relevant information exists about this terrible day except that you are dead, and I am not. But here are a few tidbits, while we’re digging up graves here today.

Putting me onto a back-board, the first responders didn’t know if was hurt or not. I shouldn’t have been alive period, probably neither should Jack nor Alvy. The bright sunlight in my eyes. The heat. May was hot that year, or at least it was on that day. The ambulance ride. The emergency room, how they checked me out. The cut on my forehead, stitched up by a plastic surgeon who looked as though he’d come in from the golf course, which I’m sure he had. I wasn’t really hurt otherwise.

Another doctor looked down as the plastic surgeon worked. How are you going to fix that, the doctor asked the plastic surgeon. Watch this, he replied. He did something, made a little stitch on what I presume was some flap of skin. Huh, the other guy said before walking away.

You’re a lucky man, a kind nurse said.

I don’t know what I said—maybe nothing. Perhaps I wept. I don’t think so. I was in shock. I found out that shock means you don’t feel much of anything—you’re floating alongside your emotions.

In my novel I wrote about all this, however, the mad, drunken protagonist Devin Rucker exhorts the kind nurse to go and fuck yourself, you whore. Such a threat seems more dramatic. But of course Devin would say that. But he’s not me, he is his own person, which means I have done a good job of writing. I wouldn’t have said that even if I had thought it. I’m not that kind of guy. Devin, on the other hand, a fictional construct, is a vision of who I might have become had I let madness overtake me in the wake of the accident.

Who should I call for you? the nurse asked.

My parents, I replied. I gave her the number.

She left me alone, then, naked underneath the sheet and covered in dried blood, all my own.

There was a commotion, shouting, activity; more accident victims were brought in, but from a different incident. The world has gone mad out there, I thought.

They kept me in the hospital for days.

Why? I was barely hurt—a cut. They were concerned I had damaged my heart—no kidding. I had (and have) a lump in the middle of my chest where the stern was slightly cracked, but it’s just a calcium buildup. My heart, as it happened, beat on, dogged and strong and youthful.

I didn’t get to go to your funeral.

My grandmother sat with me that day while it was going on. I asked: Ma-Maw, why didn’t you go to Allyson’s funeral?

Oh darling, she said. I want to remember her the way she was.

I said nothing in response. But I probably thought the same thing that I’m thinking about you now, which is, Well, that’s a luxury I’ll never know.

That night close friends all gathered and sat with me, a hospital room full of people laughing, talking, a party. Not really—they wanted to make me feel better. They did. Faye, Carlotta, Doug, Larry, Daniel, more folks. Thank you all. Some of you are gone now too, and that is a shame.

Most of all, Allyson, I write this letter not to dwell on the horror or the grief, but because I want you to know that I still love you, still think of you every day—in fact, I begin my day by venerating all those loved ones I have lost. I have given your image in my mind a beautiful yellow-gold light like a perfect cartoon sunrise, perhaps chosen to counteract the horrid unlucky tint of the paint on the Mustang.

We went from sixty to zero, both literally and otherwise after a drunk driver on the wrong side of the interstate crested a hill on a Mother’s Day Sunday morning and ran head-on into us. The vehicles both bounced four feet into the air, they said. It was the above the fold story in The State newspaper the next day. I didn’t read it at first. Doug told me about it. Said the reporter had seized on the angle (and the irony) of the fact that we were on the way to put flowers on your mother’s grave. Doug was the first person I saw in the hospital. (He almost died recently too. But he didn’t.)

I thought about killing myself there in the hospital. I was alone, sitting in the chair by a narrow, reinforced window, holding the butterfly necklace I’d given you. (Your sister Esther asked if should leave your engagement ring on your hand to be buried with you, and without hesitation I had said yes.) I looked at the window, at the ground four stories below. Not so that we could “be together” or some other such supernatural nonsense people let themselves believe so the enormity of death doesn’t overwhelm their minds—but because, ever self-aware and reasonably intelligent, I asked myself:

How are you going to live with what you have seen?

Even today, now three decades later, I’m still answering this question.

As you know, Jack survived and thrived despite internal injuries, a crushed pelvis, other broken bones. But alive. I’m betting his body aches like hell when there’s weather coming through.

I wouldn’t know—I lost contact with him and all your family, and quite intentionally on my part. I know they think ill of me—they must. But I had to. I couldn’t look at their faces anymore, not if I was to stay sane. I had to shove all of that out of my life (or so I felt at the time) or risk madness. Your sister Esther, whom I love and miss, kept in touch through the summer. We would talk on the phone.

I want you to come to Charleston, she said, and spend the weekend with me. Not like in a romantic sense, of course. I don’t really know what she wanted to say or do while I was there. Just to be close to someone who had been close to you, perhaps?

Okay, I lied. We’ll do that real soon.

I never called her back, ever again. I’m sorry, Esther. I’m sorry to all of the Ray family for taking away your beautiful daughter, but not returning her whole and alive. When I look in the mirror, I remember this failing above all others. Thirty-two years now is a long time to love and miss someone. I hope that is sufficient punishment for my numerous failings. It certainly feels like it.

The people who know this story may ask the same question as before:

How do you live with what you have seen?

I can tell them that Jenn—you called her Jennifer; you were best friends all through childhood, but I don’t have to tell you that—saved me, made my life whole, healed me, and that is the principal reason I’m here to type these words today. I hope that you would be glad we found each other in the wake of the tragedy. You both loved each other, and hope you would be glad we have been so happy together.

Alvy was all right in the end, too. The man who had taken her from me followed the ambulance to the hospital, left a note with the ER personnel so that I would know how to find her. She lived a long time, until October 22, 2002. She had renal failure, and we had to say goodbye on a Saturday morning and then go on to work at the little retail shop Jenn and I own together.

Losing my beloved pet felt like the worst morning of my life since the day of our tragedy. I said, Well, that’s the last of Allyson, now, gone forever. Alvy was the last link.

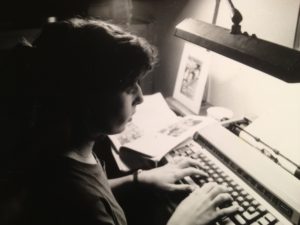

The last photo, working at my typewriter on a term paper only days before the accident.

I have had many successes and love and friendship, but a little light went out of my heart once Alvy was gone. She was a testament to my own survival. But cats don’t live forever, and neither do people. We are there, and then not. I have seen it with my own eyes. I have seen it in your face.

But you will live on, my love. You will live in my heart and mind as long as I do. I think of you every time I hear that Pretenders song:

I found a picture of you; those were the happiest days of my life…

And that is what happened to you—to us—on May 10, 1987, a thousand centuries ago—and yet not. I write this to remind myself of your glory, your beauty, your love and affection; I write this to remember.

Yours,

Donnie

About dmac

James D. McCallister is a South Carolina author of novels, short stories, journalism, creative nonfiction and poetry. His neo-Southern Gothic novel series DIXIANA was released in 2019.

I never knew what happened. Thank you for sharing your soul.

Thank you, Sebrina. Much love.

Donnie… That was so touching. I think of Allyson on Mother’s Day. Thank you for sharing your heart.

Allyson was such a beautiful person. She got stuck with me one Saturday at a Bike-A-Thon in Lugoff in the early 80’s. May have even been 1980? She was a little older than me but we were both just kids at the time. Our parents were friends & the ones responsible for making the decision that poor Allyson would have to watch over me all day. I met her that morning for the first time. She seemed so much older & so very pretty. I remember feeling scared & wanting nothing more than to go back home. I just knew that she would surely hate me because who in the heck wants a little kid like me dragging them down?? As soon as we started pedaling & out of our parents sight, she started smiling & talking with me as if I were her equal, her friend. As if we’d known each other all of our lives! We talked & laughed all day. Allyson made me feel special. She made a day of pedaling until we thought our legs were going to fall off, one of my best childhood memories. Unfortunately, I never told her how much that meant to me. She touched my life in such an amazing way. I now know that I met an angel on earth that Saturday, so many years ago. For that, I’m thankful & consider myself truly blessed. God bless you, Don. Thank you for sharing your story & allowing me to voice mine …

Thank you so much for that little story. Allyson was so full of kindness and love. The world has been poorer without her in it.

To lose someone you love is never easy, to see her in the state you witnessed is horrific. Your story is tragic, but somehow you managed to move through the hurt, what you saw, what you knew would never be. My daughter found my father after he’d been dead for days and was decomposing. She was 14, she has never gotten over that. She’ll be 29 this year. It’s heart wrenching to see that kind of pain, to know no one can ever feel what you feel, to make it okay. There are people, like Jenn, who come into your life and show you that you can be happy again, you can love again. So I’m thankful you two have each other and I know Allyson is happy knowing you found peace and love again. Take care Donnie, (sorry, it’s all I’ve ever called you!) And thank you for today and our chat and the book!! Hope to see you and Jenn soon!!

Bless you for your kind words, Lori. Seeing you always takes me back to a happy time in my life! Come again anytime.