DIXIANA Preview: The First Chapter

It had to happen eventually.

That’s right—the ebook publication of DIXIANA Book One: Dirt Surfer approaches silhouetted on the twilit horizon like a far-off rider, battle-weary but proud and erect and nearing ever closer to home. This literary hero’s journey—separation, initiation, and return—is at its conclusion.

For those of you who have followed the creation of this saga in posts like this, I know you’ll be relieved to hear it’s finally time for the actual text of this epic “neo-Southern gothic” novel series to start trickling out. Long road, couldn’t have done it without you all, et cetera.

So in that cheerful but fatigued spirit, here at long last I present the first chapter and with it, the introduction of our protagonist.

1. Roy E. Pettus

With the curvature of the Earth in evidence and a scrim of fading daylight bending around the edges of your vision, this epic vista, observed from the cockpit of your hobby aircraft, fills you with dread instead of wonder.

You’re in trouble. You don’t fly at night.

A pair of hands, in reasonable control on the yoke of the Piper PA-46-500TP Meridian—an aircraft you’ve coveted and now own and that hums and purrs along at 10,000 feet—belong to you. As per your training, your eyes sweep the visible sky and horizon in ten-degree wedges, a few seconds per wedge all while wishing to have made a few more night landings.

The eyes, burning.

Your hands, sweating.

Twilight, fast approaching.

Aside from losing the light you’re piloting fine, despite suffering one of your anxiety spells. You’ve had them since you were a little boy. Mostly under control. Until earlier in the day, upon discovering your life is a lie.

As your wife shrieked on the tarmac earlier: Roy, you are in no shape to fly.

And here, about to attempt a landing. At dusk.

Nah. Go ahead, call it nighttime. And with landings already being a weak area for you. For many other pilots, too. Seasoned and otherwise. Piloting—it can be tricky.

Face it. She was right. You are in no condition to fly.

A leathery, mustachioed father figure, Captain C. W. Gracern, an ex-military flier from whom you’d taken your first lessons two years ago, had emphasized every pilot’s goal: returning the aircraft to the ground.

“Every comfortable landing succeeds from an approach that’s stable, tracking the runway centerline down the glide path to touchdown. Everybody slapping each other on the back, and it’s Miller time, and another few hours logged. Best-case scenario.”

Prayerful, he held his hands in front of an outdoorsman’s weathered, tan face. “Worst case?”

You and the others sensed a pall settle over the classroom. But nobody spoke.

Gracern smiled. Nodded. “Damn straight—we don’t wanna say it aloud.”

The teacher had ambled around the desk and leaned his stubby body on the edge. “During the all-important approach, if a pilot’s lax in achieving and maintaining stability early enough, if at all, he’s courting trouble. Hoping and wishing for critical details to fall into place on their own—is that how we want to fly?”

“No.” The breathy syllable had escaped your lips.

Gracern, winking at you. “Right. Thinking it’ll magically come together, and that bird’ll find itself back on the earth again? Yeah; no. I can already picture the NTSB team preparing to scour the accident site.

“So listen. Stabilize early. Remain alert for deviations, however minor, from the desired course, glide path, and speed. You need more stability? Adjust—with a light touch, now—the power and-or flight control inputs.”

At the time, none of his words held quite as much weight—you hadn’t yet piloted. But they do now.

As though reading your mind, he said, “You want a real world example? Watch the big planes. See how they do it.” The instructor hooked a thick old man’s thumb out the window of the community college where you took the flying classes: “A jetliner pilot’s goal is minimal rolling and pitching, all dependent upon external conditions. Their engines? They ain’t throttling. Or they better not be, anyway. Not with all those souls onboard, those fliers under our heroic pilot’s care and control. Settle that bird into ground effect, and then? Home again.”

The class breathed a sigh of relief. You realized you’d been gripping the sides of the desk.

Ground effect, now you understood what he meant: that glorious floating sensation as your wings draw toward the blessed earth below, and the return to safety.

You’ll know the feeling soon. No magical thinking—you’re Roy E. Pettus. A captain of your aircraft, and your life.

Complete awareness.

Total control.

Except for the explosive situation you left on the ground—the shrieked accusations, the threats of recrimination. Her weak-sauce denials—the phrase ’red-handed’ comes to mind—continued to echo inside your cans during what should have been a routine flight. Your life, it occurs to you, may not be ’routine’ again for quite some time.

Expecting an imminent return to the tangible bedrock awaiting the touch of your wide, sport-sandaled chunks of feet, you grasp and cling to the bound leather stick. Maybe pray. A little.

You wipe a damp hand on your khaki cargo shorts and grab the radio to signal for the airfield lights using an on-off automatic radio sequence. At a low volume airstrip such as podunk Edgewater County, lying a hundred-fifty miles due north of Sedge Island where you and your wife live, no tower crew anticipates your landing.

Key 1-2-3-4-5. Flick the sequence with your thumb. Easy peasy.

But the lights, which ought to be ahead of you, are nowhere in sight.

Without the airfield landing lights, and with your limited flying time at night, you need to get wheels down.

On the ground.

The Mercedes would have eaten alive the concrete of the freeway. But you didn’t drive, and here you are. You had to fly, didn’t you? To get away from her fast.

The airfield beacon—there, you see it. Flicking the thumb sequence again, you wait.

No landing lights.

Calm down; it’s not as though you’re in bumpy weather or having trouble like in a movie; this isn’t a modern version of Airport 1975.

You flick the sequence again, with deliberation.

Nothing.

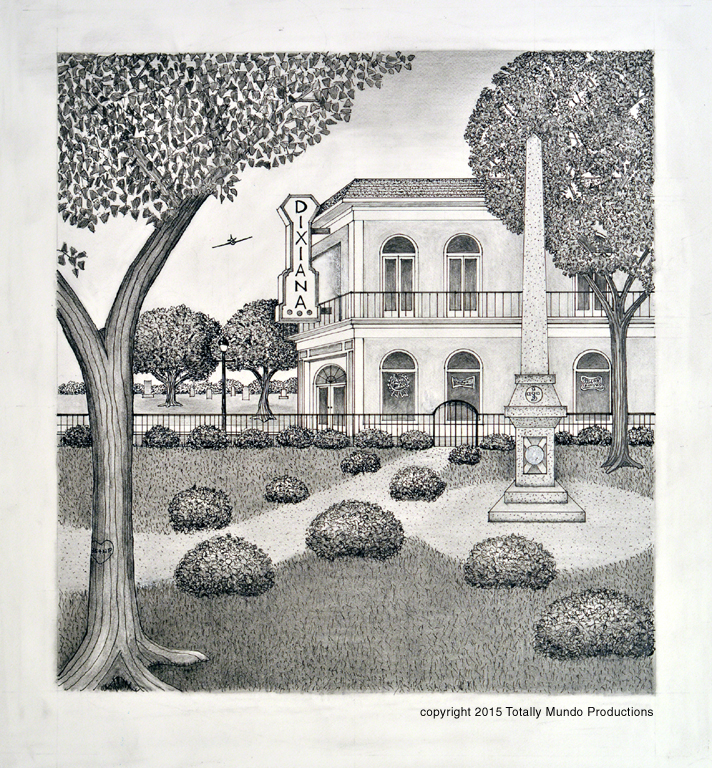

Cruising now across the fall line, high above Edgewater County here in the uppermost of the state’s midsection, your dusty old hometown sits off to the right, closer to the river. You can see the lighted town green, its trapezoid shape and big oak trees, the courthouse, the highway bypass skirting downtown. Soft, amber street lamps illuminate the neighborhoods. But no landing lights.

A different beacon jumps out at you: the neon sign glowing orange outside The Dixiana, your granddaddy’s honkytonk.

Home.

At least you’re not over water. Whatever happens, you won’t end up being remembered as the JFK, Jr., of Edgewater County. Calm winds, a clear September sky—clear as 9/11.

But now, the sun, gone.

And no landing field lights.

You, Roy E. Pettus, need wheels down. And fast.

An extravagance, the aircraft.

You’re not wealthy, not by the standards of the day. No, you’re only flush. A billion, that’s what’s cool. You’re only a million. A few million. Not rich. Cash rich and without liens of significance, with wealth compounding more wealth and the stock market hitting new highs every month, your ass sits in high cotton.

But not like, rich-rich.

Still, enough you could afford the Meridian. Deserving a rich man’s toy like this. Had outgrown your first plane, a used Piper Cub that rattled like a death trap. Had outgrown it in more ways than your flying hours, had deserved the finer appointments and details of the Meridian, as befitting the size of your wallet.

Now, a few of the swells you know from the hanger are big big money. Carry themselves that way. But in the hanger, where you all have flying time, you dwell among peers regardless of fortune.

Tin cans with wings, as you and your buddies in the airfield lounge call your personal pleasure aircraft arrayed along the tarmac and under the sheds. You and the boys gather to shoot the shit either before or after flying, the way the stiffs congregate on tennis courts and golf courses and in the many exclusive clubhouses found in a magical land like Sedge Island. You dig your hobby, big-time, but flying also makes you claustrophobic, a little breathless. Not as much anymore. Not since you got in your hours and began flying your own plane, and in those moments feel like the captain of the planet, not at all anxious.

Until this flight.

Brutal. Horrifying. You are in no shape to fly.

You’re airborne not simply to escape your wife, Creedence.

On your way.

To attend to your dying grandfather.

At last.

Don’t be like that. How cruel.

But you can’t help it. Pushing ninety, both Mama Runelle and your granddaddy. It worried you, having old-timers of such vintage on your sheet. A miracle they still lived on their own. No broken hips, no major illnesses or injuries, but still frail. Why you built them a house with an upstairs is a mystery—they don’t need the room.

Lord knew you wondered what kept them going. Him, in particular.

The hell you wondered—you knew he wouldn’t be happy unless he croaked sitting outside on that bench beside the entrance to that honkytonk of his, the wretched old dump you couldn’t stand to think about getting near.

But yeah, this fresh crisis came at a bad time, no doubt. As far as the implosion of the marriage goes, the catastrophe loomed so fresh you literally flew away from the last confrontation, which had come earlier today like a black swan event in the markets. In the context of the day so far, the news of your grandfather’s purported heart attack at The Dixiana, or wherever it had happened, came inopportune and unwelcome, while also long overdue—if he wa’n’t careful, the old fart might find himself in triple digits.

Into overtime.

Another ten years? Forget it—the codger still smokes, for god sakes.

If he dies, as you thought upon hearing the news which rippled into your thoughts through the brackish marsh water of betrayal surrounding your marriage like the ugly stalking snout of a gator, maybe you can let go of some of that Edgewater County energy you’ve always been certain has held you back all this time in some obscure fashion.

You didn’t know such release would involve losing Creedence, too. Did ya.

The twanging strains of a hundred old country songs about betrayal and heartbreak earworm their way into the soft gray meat of your mind. You rued enduring such music during your youth at the honkytonk. Every syrupy melody, every minor key lament, all overlaid and reverberating like a hollow soundtrack to a simmering cauldron of gut-sick disappointment at how your life has turned out, at least on the relationship side of the coin.

For all your successes, you still haven’t shaken off the past. Not that marrying a hometown girl, a childhood crush, helped in that regard. You owned the house on Sedge Island and loved that selfsame beautiful wife, and what’s more, had cashed out at forty-seven. Your net worth in stock and assets, brushing up against eight figures.

But you feel held back, still.

From what?

Your grandparents still alive here in the almost-upstate. Perceiving their energy tugging at you.

You thought by now they’d be dead, and The Dixiana would be closed, and you’d sell the house you built them a decade ago across from the more modest ranch house in which you grew up, and for a sick, sick profit. Dump the houses and the land, every square inch, all the way over to the pecan orchard and into the backland toward the river. Donate every lick of the proceeds to charity, like Creedence’s animal rights groups, or maybe the old alcoholic’s home in Edgewater County.

Now there, an idea—wouldn’t that constitute spiritual recompense for the decades of drunks your granddaddy’s tavern had served, including your wife’s dead brother, the pitiful sot?

Spiritual recompense. You don’t even know what the words mean.

Coming around for another attempt at landing, you twinge as you recall a fantasy you’d had of trying to goose matters along: you considered hiding in their bedroom closet, waiting to pop out in a black robe and holding a scythe. You know, a cartoon-ish Mr. Death like in the Monty Python skit—there’s a man at the door, something about the reaping.

Well well, a voice chastises. It’s here now, isn’t it?

You awful grandson, you.

True. You’d felt so guilty over feeling this way you’d built them a house, more house than they needed, a situation not unlike you and your childless wife down on the island. A coldly tiled, pale stucco mansion compared to the warm, classic Victorian you’d insisted on constructing for the folks.

Back in the woods.

Like you want for yourself, in many ways.

Just not there in Edgewater County.

The voice in your head, a phantom, could have belonged in meatspace to Dobbs Vandegrift, a homie and oldschool hombre from whom you received the call about Rabbit. Dobbs, one of your oldest friends, in this case calling to break bad news. When you heard his voice, you already knew a momentous event at hand, because neither of you spoke anymore. A significant example, years ago now, had been when he’d called to bemoan receiving a postcard from Creedence’s brother Devin, the no-good drunk who’d made an avocation of disappearing on his family, at last for real.

The postcard had read: Tell ’em it’s for keeps this time. That it’s close, getting real close. Love to you all. After eight years had gone by, you and Creedence had him declared dead.

Devin. He always had this dramatic schtick about dying young, and had come close: drunken falls, fights, a car wreck in which his girlfriend Libby had been killed, also leaving Dobbs paralyzed. Awful stuff.

Maybe Devin made the reality of all that death stuff. All his gloomy obsessions. And the drinking, Olympian in scale. What would Dr. Phil say about all this self-destructiveness?

Problem is, your wife still suffers over him, the asshole—Devin, not some television shrink. She writes letters to him, still. Saddest shit you ever heard. Problem the deuce is that, for you, Devin remains in your heart as one of your best childhood friends.

Creedence. Her grief over Devin didn’t matter to you anymore—y’all are finished. That’s the main problem. Change has come upon you, in an awful wave. Faithlessness trumps heart attack.

Wait—did it? A debate above your pay grade. Back in college, you’d dropped out of Philosophy class after only a week. Too much intangible bullcrud.

In any case, your life as it’d been, dwelling in the quiet violence of your wife’s disinterest, has been bad enough, wondering where her heart and head had gone.

Which is complete crap. You woke up this morning thinking everything fine—that’s the god’s truth right there, boy. You hadn’t a clue. Not a clue. You had dreamed of a white pyramid on a hill. You had thought it was your recurring dream of the mountain bald like Max Patch, but in this dream, as you got closer on what felt like an epic hike through lush green forests, what you kept glimpsing turned out to be a pyramid. Blue-white. You felt the presence of magic. Shimmering energetic magic, and in the dream your feet had lifted off the ground, and you’d levitated.

You’d awakened in a state of grace. It wasn’t to last. Not after reading all those emails between your wife and the lover for whom her rhetoric indicated she intended to leave you.

On approach again, the lights from the Sugeree Nuclear Station along the river, for reasons of national security a no-fly zone, fall away. Looking again for the airstrip beacon, turning turning turning, green-white-green-white. Your glasses, forgotten in the fight with Creedence at the hanger and now this, this, this, the landing strip lights still cold and dark.

Beacons all around, these last fifty miles: Columbia Metro, Van Loan Field, McNabb National Guard Base, and farther east the AFB, but all those fallen behind you now, and only Edgewater County ahead.

Flicking the thumb switch sequence on the mic again, and again.

What you wouldn’t give now for one of those guys from back at the airport on Sedge Island, eh? Older dudes, retirees who’d worked for airlines or as mechanics on the airplanes themselves or who’d been pilots, a couple claiming to have now forgotten more about flying than they still knew. What you wouldn’t give to have one of those old coots to ask what to do now.

Fried from the last battle with your wife and the revelations that’d come out of her mouth, gut-punching facts you already knew, but damn if it didn’t feel all the worse hearing her confirmations, you can’t think straight. From what you read, this, no mere fling. This crap sounds like love.

Now, this hurts, enough to make a man like you forget his goddamn glasses, which you hate wearing anyway because of the new bifocals; a grim reminder how at your age you’re more than halfway to the end: the eyes, the bad hearing in one ear, a dick not always a stiff and pulsing flagpole every morning before you rise, which is after Creedence because she’s up and at it these days, and hoo-boy, don’t you know why now.

Writing little love letters.

Maybe you can’t see the airfield lights which now flare blue and bright as ground-fallen stars, because of the smeary tears on the lenses not of the missing glasses but of your eyes themselves, crossed and burning and red—you’ve been crying ever since you took off from Sedge Island. Half-blind over it all. That’s your problem. Besides needing the fudging airstrip lights to come on.

As though a wish being granted, on the second approach you flick the sequence and the blue lights appear clear as crystal. Your self-confidence comes roaring back, and you take that hunk of tin and put it wheels down.

On the ground.

Relief.

As for whom you’ll call for a ride, wellsir, you are not one to Uber. Who lives nearby? ’Tis a shitty part of the county here, way outside town near the airstrip; this is Pirkle country, and with that in mind you rationalize reaching out to Trudy, your granddaddy’s right-hand gal at The Dixiana.

Face it: you’d be calling her no matter what. Trudy, an old love. One about whom you still dream. Jerk off to, even. Not that you’ll call about such personal matters. It had been one of those let-us-never-speak-of-it-again situations between you.

Trudy: Not only your first lay, but the first woman in whom you believed you felt love. Such as a sixteen-year-old neophyte can know what love is, especially with a redneck barmaid from the honkytonk. A few years older than you, she’s now well over the crest of fifty.

Trudy. She had been the go-code to begin a race you hadn’t run. Not until Creedence, years later.

Was it all circular? Today’s also the day I’m to come to terms with Trudy Pirkle?

Now?

In a word? WTF.

The idea of seeing her produces a bracing chill down your conflicted spine.

Trudy.

Concentrating on your flying, you approach with no lack of landing indicators or directional confusion: inexorable, your destination, looming ahead in the middle distance.

Wheels-down you might now find yourself, son. But face the facts: you’re lost, still.

Fumbling with the iPhone you kept turned off while airborne, you discover a number of missed calls—from Dobbs again, Creedence, and from your grandmother, a fragile voice calling you darling, and telling you hurrying is no longer necessary; your grandfather has passed away.

You curse and stomp your feet; you do not fail at life this way. And yet you have.

Trudy. Trudy will make this all okay.

If only your eyes weren’t so blurry, you could better punch in the number to The Dixiana, which to make some boneheaded personal point you don’t keep saved in your stupid, powerful mobile device connecting you to the whole of human knowledge.

Pitiful, Pettus.

You disappoint yourself—a web search to find out what’s now an important phone number? You’d better get it saved in your contacts—it’s the one belonging to your latest business venture, a recent acquisition: the decrepit, third-rate Edgewater County honkytonk you’ll now own. Lucky freaking you.

About dmac

James D. McCallister is a South Carolina author of novels, short stories, journalism, creative nonfiction and poetry. His neo-Southern Gothic novel series DIXIANA was released in 2019.